Strategy, and the process of formulating strategy, has changed a lot in the last 20 years. For some decades before these changes began to affect how we think about strategy, the process of formulating strategy was a standard approach which was generally based on stable and predictable environments. The examples of this in the past could be mining or oil extraction, or perhaps telecommunications before the internet. Here is a great article from HBR which suggests that adaptability is the new competitive advantage . See below a short insert from the article which says:

We live in an era of risk and instability. Globalization, new technologies, and greater transparency have combined to upend the business environment and give many CEOs a deep sense of unease. Just look at the numbers. Since 1980 the volatility of business operating margins, largely static since the 1950s, has more than doubled, as has the size of the gap between winners (companies with high operating margins) and losers (those with low ones).

All this uncertainty poses a tremendous challenge for strategy making. That’s because traditional approaches to strategy—though often seen as the answer to change and uncertainty—actually assume a relatively stable and predictable world.

In todays business environment we are increasingly confronted by challenges which are more complex or chaotic in nature. Senior leaders are finding it more and more difficult to formulate strategies that are suitable, or productive, in dealing with these complex challenges effectively. Today leaders in many companies are starting to ask the following key questions about strategy: (from the article adaptability is the new competitive advantage)

- How can we apply frameworks that are based on scale or position when we can go from market leader one year to follower the next?

- When it’s unclear where one industry ends and another begins, how do we even measure position?

- When the environment is so unpredictable, how can we apply the traditional forecasting and analysis that are at the heart of strategic planning?

- When we’re overwhelmed with changing information, how can our managers pick up the right signals to understand and harness change?

- When change is so rapid, how can a one-year—or, worse, five-year—planning cycle stay relevant?

Complexity describes the behaviour of a system or model whose components interact in multiple ways and follow local rules, meaning there is no reasonable higher instruction to define the various possible interactions. These complex challenges have not been experienced before, which means there is no blueprint on how to deal with them.

The major problems companies are facing today are complex and chaotic.

Because of globalisation, technological integration and the rising use of data analytics, the traditionally rigid and predictable organisational approach toward strategy formulation (build mostly on macro-economics) is now becoming much more focussed on what the power of data & technology can deliver in, terms of substantiated evidence, which can support and guide strategy formulation along far more detailed and specific organisational factors (over and above just macro-economic factors) that are proven and substantiated by rich data sources. However, despite this increased focus on technology and data as an additional rich source of strategic guidance there are still serious challenges presented by complex problems.

(Insert from HBR – Strategy as a wicked problem! )

They crunch vast amounts of consumer data, hold planning sessions frequently, and use techniques such as competency modeling and real-options analysis to develop strategy. This type of approach is an improvement because it is customer and capability focused and enables companies to modify their strategies quickly, but it still misses the mark a lot of the time.

Companies tend to ignore one complication along the way: They can’t develop models of the increasingly complex environment in which they operate. As a result, contemporary strategic-planning processes don’t help enterprises cope with the big problems they face. Several CEOs admit that they are confronted with issues that cannot be resolved merely by gathering additional data, defining issues more clearly, or breaking them down into small problems. Their planning techniques don’t generate fresh ideas, and implementing the solutions those processes come up with is fraught with political peril. That’s because, I believe, many strategy issues aren’t just tough or persistent—they’re “wicked.”

Not all complex challenges are truly wicked, but they do fall into a similar category of thinking when it comes to developing your strategy. In these cases strategy formulation and execution requires a serious make-over from its lofty and rigid predecessor. In order to begin this process it is vital that we all have a clear understanding of why traditional strategic thinking approaches are no longer working as well as they once did.

The presence of increasingly complex or chaotic environments (wicked problems) in which it is impossible to clearly define or understand the nature of the problem you are dealing with, has pushed strategy towards a more emergent and future state driven thinking process. The difference in strategic approach and process depends on the nature of the problem you are trying to solve. In the case of the past decades of business strategy there was a very clearly tried and tested approach towards formulating a business strategy.

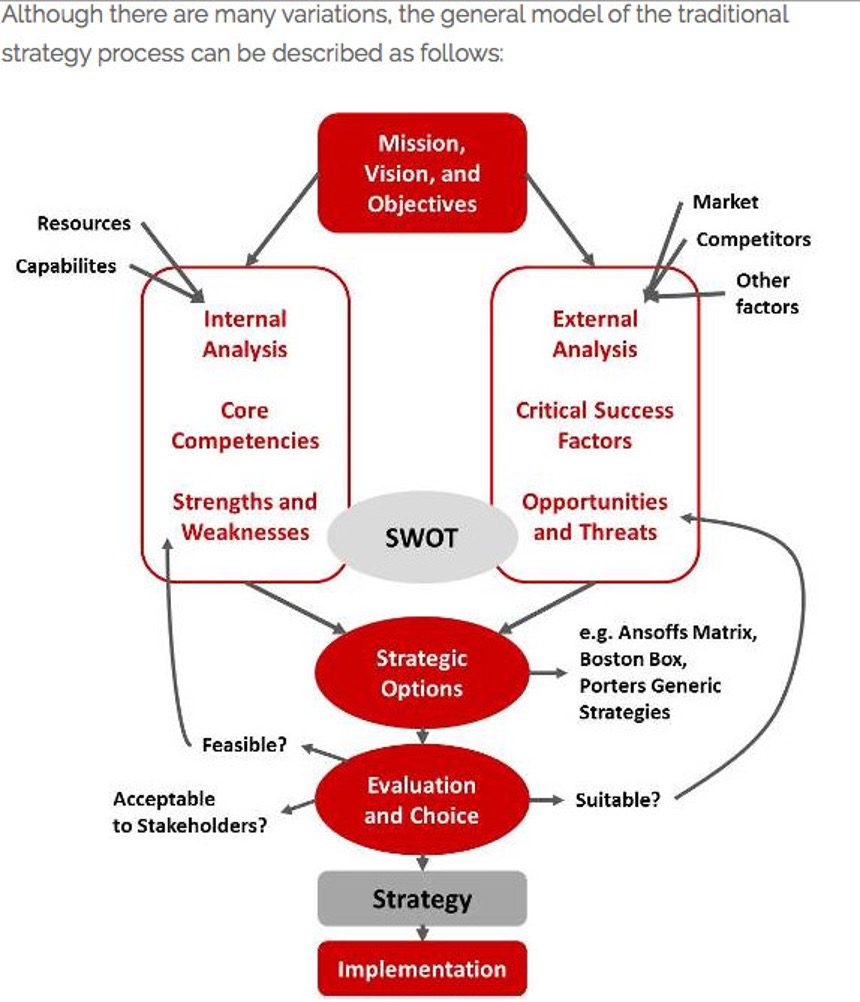

Generally this strategy lasted for 12 months, and was set in stone until its annual review. Here is a basic overview of this traditional approach towards strategy formulation and execution. This information is from www.themanager.org and comes from the article called The traditional strategy process

Traditional strategy schools of thought see strategies as a means for achieving competitive advantages and a favorable position in the marketplace. This takes place in a stable or predictable environment by exploiting competences and resources. This approach towards strategy formulation does have its benefits, especially that this methodology is commonly understood and engrained in the broader business community as accepted thinking, process and methodology.

The traditional strategy process may still lead to reasonable results in certain industries and markets. This applies in particular to markets that are not strongly affected by disruptive changes. However, as we can see this is changing fast, and your business may well be caught unsuspecting down the line.

Finally, the analysis process and the SWOT model still can serve as a way for compiling, analyzing and structuring information. Businesses are easily overwhelmed with the vast amount of data, information, explicit and tacit knowledge when analyzing their situation. The use of well-known tools can help to filter and make sense of this information overload.

Problems with this Approach

Despite these benefits the traditional strategy approach has serious drawbacks which cause unexpected, and often chaotic problems to crop up later on due to these blindspots not being uncovered or thought of at all. The original design of this process did not take into consideration todays dynamic and unpredictable business environment. It wasn’t designed for these circumstances. Hence, it won’t lead to optimal results. Problems arise from the following issues:

-

The process and the associated tools can’t keep up with the pace of change in the business environment. They will lead to lagging results.

-

Strategists are tempted to shrink their focus, due to the increasing uncertainty. Their focus shifts to internal analysis and the near-term future.

-

Strategies resulting from this process are always based on the current situation and limited to thinkable futures.

-

The growing number of viable future scenarios makes it a lottery to decide for a strategy that fits one particular future.

-

The strategic plans may be too inflexible for today’s pace of change.

-

Strategies are based on and limited to the pre-determined corporate vision, mission, and objectives.

The Big Shift in Strategy

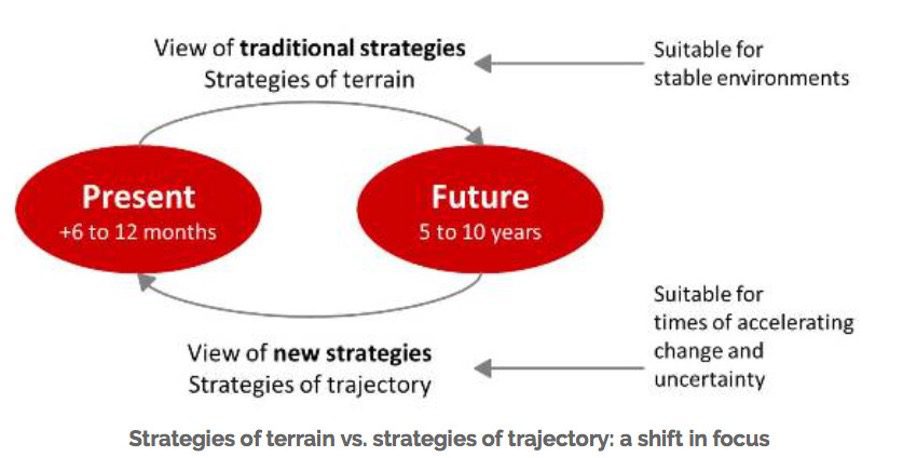

The big shift is that new strategies should focus on the most attractive and advantaged positions in future landscapes, not the current landscape.

He also provides five elements to successfully develop such strategies of trajectory:

-

Challenging: to “unlearn” some of our basic beliefs about how the world works; scenarios are a good approach here

-

Shaping: to ask which future is most attractive and then to take actions to shape the probable future into that direction

-

Motivating: to motivate people to overcome risk averseness and to take bolder action

-

Measuring: to measure the progress in a particular direction; don’t focus on lagging financial indicators – find suitable operating metrics that are leading indicators

-

Learning: to reflect on the experiences from the progress so far and to adjust further actions accordingly

Successful strategy in today’s world is all about finding the right approach to deal with different categories of problem. Modern strategy uses a few clear guidelines and allows for flexibility and adaptive thinking and design. It is supported by organisational design and processes; and it is not handed down from on high as a mandate for others to deliver on, but rather co-crafted and designed by a range of employees, customers and strategic partners, all of whom form part of the strategic development process.

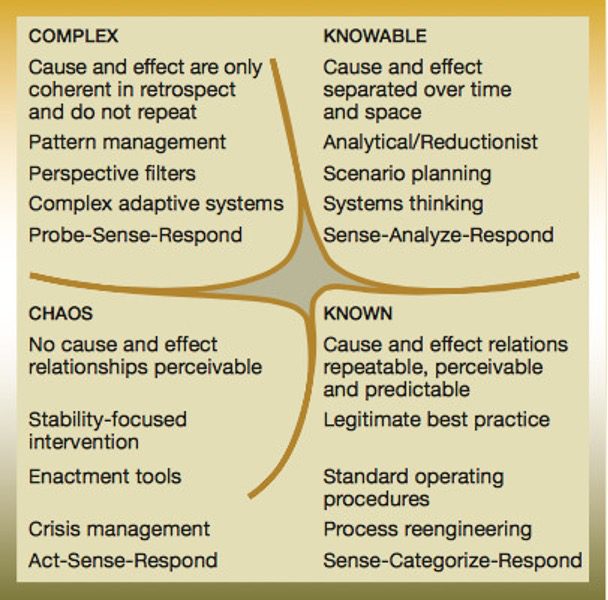

Many leaders are only to quick to define the organisational problems they face as simple or complicated, which either allows them to dismiss the problem as small and easy to fix, or it allows them to rely on external consultants and experts to fix things that these leaders do not understand.

It has come to light in recent years that simple and complicated problems are the least of our worries. Yes these problems are still happening, and still require intervention, but there is clearly a far more important requirement for leaders to get to understand newer and emergent problems which do not fit within the simple and complicated domain. These problems are complex and chaotic and they do not follow the same rules and processes to solve them. These varying problem states are best illustrated by the Cynefin framework, designed by David Snowden.

As you can see there is clearly a vastly different approach used to solve each problem state. Without a clear separation of organisational issues into these categories, it is highly likely that your organisation is applying the incorrect thinking, processing and problem solving methods to the wrong problems, which can only lead to incorrect and erroneous outcomes.

In order to get into this strategic mindset your organisation needs to commit to making clear sense of its environment, and the priority problems within this environment. Too many organisations are convinced that they know everything, which suggests they are unlikely to be asking key questions about their situation.

Before we devise and deploy any strategy, it is crucial that the organisation in question has spent enough time making sense of itself and its circumstances in relation to its external environment.

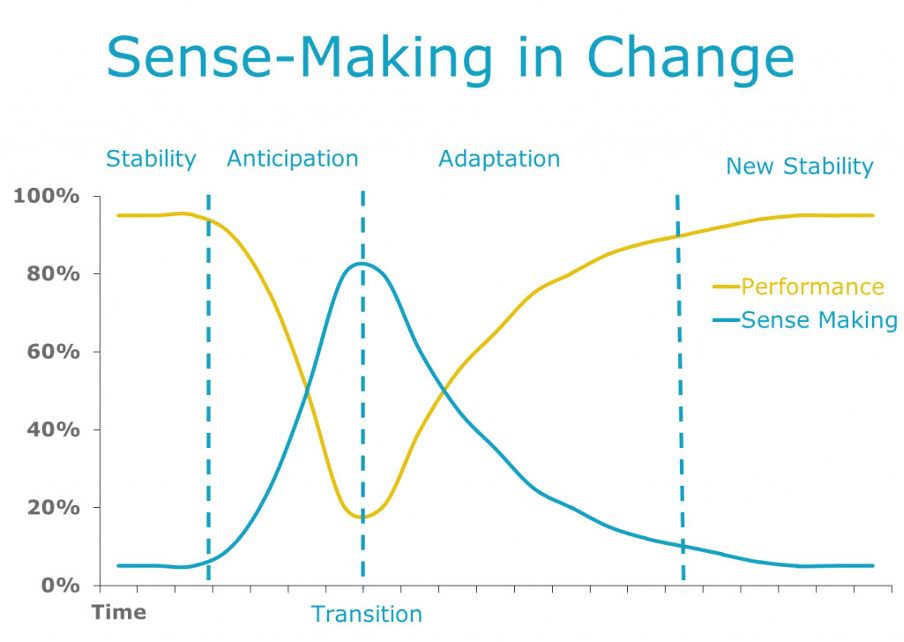

Sense making is a process which achieves the following important pre-causal conditions in which an organisation can gain a better view of itself, its problems, and its potential solutions.

- Sense making describes the negotiation and creation of meaning, or understanding, or the construction of a coherent account of the world according to your business.

- Sensemaking is matter of identity: it is who we understand ourselves to be in relation to the world around us.

- Sensemaking is retrospective: we shape experience into meaningful patterns according to our memory of experience.

- How and what becomes sensible depends on our socialization: where we grew up in the world, how we were taught to be in the world, where we are located now in the world, the people with whom we are currently interacting.

- Sensemaking is a continuous flow; it is ongoing, because the world, our interactions with the world, and our understandings of the world are constantly changing. You might also think of sensemaking as perpetually emergent meaning and awareness.

- Sensemaking builds on extracted cues that we apprehend from sense and perception. Cognition is the meaningful internal embellishment of these cues. We articulate these embellishments through speaking and writing – the “what I say” part of Weick’s recipe. In doing so, we reify and reinforce cues and their meaning, and add to our repertoire of retrospective experience.

- Sensemaking is less a matter of accuracy and completeness than plausibility and sufficiency. We simply have neither the perceptual nor cognitive resources to know everything exhaustively, so we have to move forward as best as we can. Plausibility and sufficiency enable action-in-context.

Sense making relies on the emergence of insight and knowledge from processes which illicit meaning and understanding of organisational dynamics, and the related dynamics of its environment.

This approach towards understanding the organisation is directly opposed to the more common method of predefined opinions and solutions which are not based on finding emerging insights and answers through organisational wide problem solving, but rather on limited and often unquestioning opinion of a few select leaders who think they have all the answers, and are not willing to question their own logic and thinking openly among their colleagues.

David Snowden suggests that sense making is the new approach to formulating strategy in a complex and chaotic world. Sense making is also a key process in dealing with and managing change, which is exactly what is required when a new strategy is formulated. It is our organisational ability to adapt, manage and traverse these changes which provides the potential for new strategic horizons to become actualised.

In Conclusion

Too many companies and senior executives are not connected to the changes affecting the stability of their operating environments. These companies continue to apply strategic methods and plans which are no longer relevant in solving our currently evolving and complex organisational problems. It seems to me that it is much easier for strategists and leaders to use traditional methods of strategy, because these well-known methods are ingrained in our common understanding and process of doing things, and we have been doing it this way for decades so why change now?

Many organisations (probably unconsciously in many cases) reject new strategic thinking in favour of tried and tested and slow matured. These tried and tested approaches to strategy are quickly proving to be less than adequate in dealing with complex or chaotic problems, which are the problems that are causing the most disruption and confusion in business today.

Much of this resistance towards adaptation to new thinking is rooted in a fear of change. It also rooted in the fear of organisational and personal failure. It is clear that if our organisational leaders do not begin to adapt towards new strategic thinking methods and approaches, there will be major failures happening anyway (and they already are in a big way), because these supposedly unique and differentiated traditional strategies are failing to take into account the most important factors of modern strategy – instability, uncertainty and unpredictability.

The required change in mindset is huge! It requires executive and experts to say “we don’t know what the answer is, we will have find out” which is a very uncharacteristic perspective for many senior leaders and experts who seem know everything and are not willing to be vulnerable by ‘not knowing’.

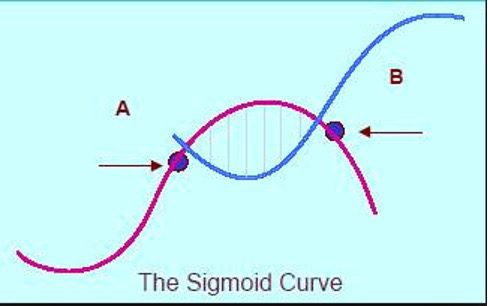

The sigmoid curve suggests that in most cases organisations only start to change their tac when it is too late (point b below), when resources, energy and motivation to change is decreasing. In order to capture new growth and to sustain existing momentum it is crucial that organisations are able to spot the early warning signs that change is needed. The ideal time for this to happen is when the organisation in question is still thriving and is motivated and energised by its current success (point a below).

Despite this reality many organisations cannot find the early warning signs or markers (both internally and externally) which indicate that change is required now, which means that they carry on going on their set trajectory without considering strategic alternatives. This is the problem of traditional strategic thinking.

It is the heightened awareness, knowledge and skill of leaders and strategists to develop sense making skills which allow them to elicit the early warning signs, and which allow them to focus more on alternative future states in which new growth or market share can be captured successfully.